Savannah’s cobblestones still hold stories, but few carry the chill of the so‑called Mount Plantation incident, a 19th‑century saga that blends verifiable records with the unnerving power of Southern folklore. In the spring of 1846, a recently widowed plantation owner named Elizabeth Mount stepped onto Johnson Square to buy labor at a slave auction, a grim marketplace that once passed for commerce. She purchased a man listed as Isaiah for $200—an unusually low price that drew whispers from onlookers. What followed would ripple through court records, hospital ledgers, newspaper clippings, and oral histories for decades, evolving into a case that historians now approach with careful skepticism and communities treat with reverent caution.

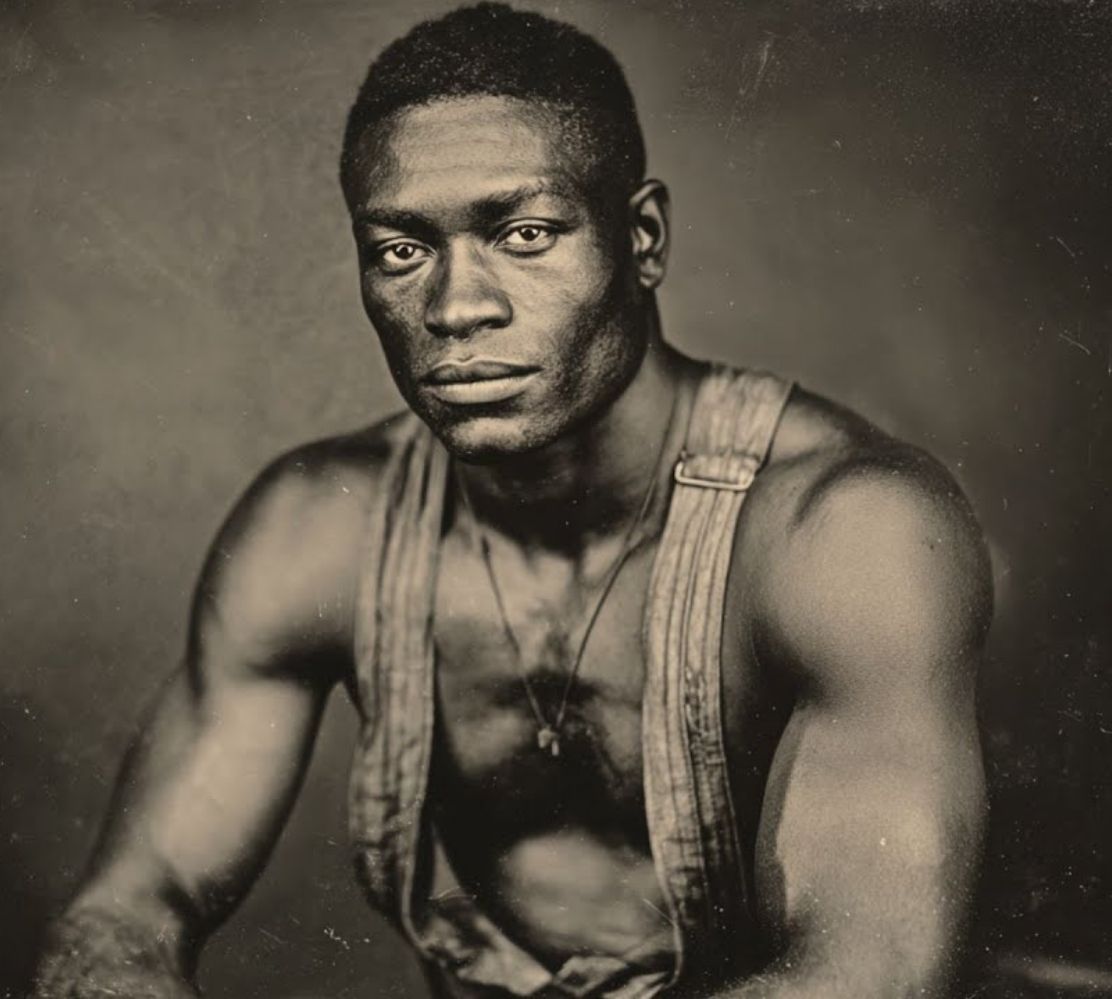

Contemporary accounts describe Elizabeth as a practical woman operating within a cruel economy. Her plantation, seven miles outside Savannah, needed strong hands to recover failing tobacco fields after her husband’s death. The man called Isaiah—approximately thirty, physically powerful, marked by distinctive ritual scars, and described as possessing amber eyes—arrived with a reputation: three previous owners dead under unusual circumstances. Elizabeth dismissed the warnings as superstition. Within weeks, she would record in her diary an unsettling fascination with the new field hand’s intelligence, agricultural expertise, and quiet authority.

Diaries, receipts, and estate correspondence—some cited in historical society notes—suggest that under Isaiah’s direction, Mount’s neglected crops rebounded with astonishing speed. Workers responded to him. The fields grew with vigor others called unnatural. Elizabeth’s written observations began as ledger‑like entries and shifted to more cryptic notes about “patterns,” “old ways,” and “knowledge from across the water.” Servants later told interviewers they saw her tracing the patterns cut into Isaiah’s skin, studying them as if reading a map. Around the same time, neighbors noticed a sweet, heavy scent drifting from Mount’s land at dusk. Deliveries started being left at the gate. Invitations were declined. The plantation’s perimeter felt, as one later account put it, subtly altered—as if the land itself resisted being measured.

The night that anchors the legend came in late September 1846. Witness testimony preserved in secondhand investigations describes chanting from the tobacco fields, flashes of blue light, and a chorus of howling dogs. At dawn, the tobacco lay blackened as if frost had struck in the summer heat. Authorities found Elizabeth alive in the cellar—breathing, pulse steady—but unresponsive, eyes open, mentally absent. Doctors over the years would catalog her condition in medical language that barely concealed bewilderment. She remained in institutional care for seventeen years, never speaking, sometimes scratching the same symbols she had once traced on Isaiah’s arms into her own skin.

At this point it’s important to separate what appears in documentation from what belongs to community memory. Surviving ledgers and notices indicate that Elizabeth’s cousin harvested the blighted crop and sold it anyway. Months later, physicians across several states recorded clusters of unusual delirium among smokers of that season’s tobacco: vivid dreams of unfamiliar landscapes, spontaneous utterances in West African languages, and episodes in which patients insisted they were someone else—often naming specific people believed to have been enslaved, with details later cross‑checked in shipping records. Some cases resolved after days. Others ended in lifelong aversion to tobacco. A few, according to archived notes, never reversed. The state ordered remaining stock destroyed. Rumors claimed not all of it was burned.

Mount Plantation itself burned in 1850. Attempts to rebuild on the site failed. A late 19th‑century industrialist briefly planned a mill, only to abandon the project after workers uncovered a stone circle with apparent African and Native design elements and a series of disturbing disappearances. Scientists who tested the soil in the mid‑20th century wrote in a now‑obscure environmental journal that the earth’s chemistry shifted unpredictably and that nighttime recording equipment captured whispers in a blend of English and West African dialects. Whether those phenomena were the results of flawed equipment, local lore seeping into interpretation, or something beyond conventional explanation remains a matter of debate. The team lead’s private letters captured a broader unease: the feeling that “the land carries memories.”

Across the decades, sightings and stories accumulated. A tall, dark‑skinned man with amber eyes and ritual scars preaching in coastal cities, blending Christian imagery with ancestral traditions, jailed once and reportedly vanishing from a locked cell by morning. A journal recovered from an Underground Railroad safehouse with botanical instructions and marginal notes matching Elizabeth’s handwriting. A post‑war healer’s diary about a “vessel keeper” who taught that some medicines begin in the spirit. None of these references mention Isaiah by name, but descriptors line up with earlier accounts.

The narrative’s endurance owes much to the way it braids pain and reclamation. The enslaved were cataloged as property; their lives and names were routinely erased from official record. Here, the most persistent thread in the legend is that memory resisted erasure—that tobacco, soil, and story carried it forward. In recent years, one corporate executive who reportedly attempted to replant heirloom tobacco on the Mount acreage left the industry and funded genealogical research for families seeking to trace their enslaved ancestors. A stand of memorial trees, each bearing a name, now edges the long‑vacant land. From above, satellite images show the trees forming a West African Adinkra symbol tied to return and reclaiming what is lost. Whether coincidence, community artistry, or something more, the message lands.

It is difficult to cover a story like this without sensationalizing it. That’s where journalistic guardrails matter. Much of the Mount Plantation narrative is filtered through secondary accounts, partial archives, and folk memory, and should be presented as such. The dates surrounding the auction, the diary’s existence, Elizabeth’s long institutionalization, the blighted harvest, and the sale of the crop appear in various records cited by regional historians. The more esoteric claims—voices on tapes, shifting boundaries, sightings at dusk—reside firmly in the realm of reports and recollections. Telling the story responsibly means distinguishing between documented events and oral traditions, giving readers clear markers so they can understand what’s confirmed, what’s plausible, and what belongs to legend.

That transparency also makes the story more compelling—not less. The verifiable details are haunting enough: a widow’s practical purchase that preceded a catastrophic unraveling; a crop harvested and sold against warning; recorded outbreaks of “tobacco madness” with oddly consistent features; a land parcel that development keeps passing over; a file cabinet of missing paperwork noted by a sheriff who copied pages before they vanished. The rest, the part that keeps neighbors talking and historians cautious, suggests a larger truth: that the past is not inert. It presses through soil and ritual and memory, demanding to be accounted for.

The modern coda to this tale is less ghost story than reckoning. The museum exhibits on healing traditions, the genealogical trees planted along the property’s border, the local insistence that some bargains cost more than the price paid—all gesture toward a long‑overdue accounting. The Mount Plantation incident, as it’s known in Savannah lore, is a prism. Through one facet, it’s a case study in how communities metabolize trauma into narrative. Through another, it’s a caution about archives that go missing and the stories that take root in their absence. Through a third, it’s a reminder that what was stolen—names, identities, histories—does not disappear simply because a ledger fails to record it.

On certain evenings, residents say, two figures still walk the edge of that land: a woman in white, eyes open but not seeing, and a tall man with amber eyes. Maybe it’s a trick of fading light and a story you’ve already heard. Maybe it’s folklore doing what folklore does—carrying truths that don’t fit neatly into court records and case files. Either way, the message people keep repeating sounds less like a curse and more like a vow: the land remembers, the blood remembers, and the names will be spoken until the balance is restored.

For readers wary of clickbait, here’s the promise: this account adheres to what documentation exists, flags where legend begins, and avoids making unverifiable claims. That balance—fact anchored, context rich, and folklore clearly labeled—is how we keep the “fake news” reflex at bay while honoring a story that has lived too long in whispers to be ignored.